To the right is a simple diagram of three pencil points that I know of. I'm sure there are more.

I've attempted the flat head (1) with a Prismacolor Premier graphite pencil, but it’s too thick (~5mm) and too hard for that sort of drawing. A charcoal pencil (2mm) might be a better choice.

The more common shape I’ve

been seeing is a sort of rounded edge (3) used by Vilppu, Proko, and Karl Gnass. The idea is

to round the graphite in such a way that the more you tilt it, the thicker the

line you draw. If you hold it in the normal, calligraphic, over-the-palm way,

you might as well be drawing with (2). So, they recommend artists hold their

pencils under-palm in a manner Karl Gnass demonstrates in this video. A thin

line can be achieve without tilting the pencil on its head by simply turning

the pencil like a paintbrush. Drawing in this way also helps to keep the pencil

sharp, which improves workflow.

The

problem is—and I’m sure I’ve said this before—learning to hold the pencil

under-palm is like learning how to draw all over again. I guess it would be

easier if I’d been working with paintbrushes up until now. I can appreciate the

purpose of this exercise. The point is not to think of the pencil as putting ‘ah line on teh page,’ but as a tool for

making marks, so you ought to get comfortable with holding it in whatever way

makes the mark you want. It’s easy to learn this with brushes, since we were

never taught how to hold them in the first place. So you see people holding brushes like pencils and sometimes holding them like a chopstick and tilting them

in whatever direction to paint in that direction. A good sketch artist has to

learn to do that with a pencil.

But

it’s a pain in the ass, and I might save time in the long run by practicing it now, but that

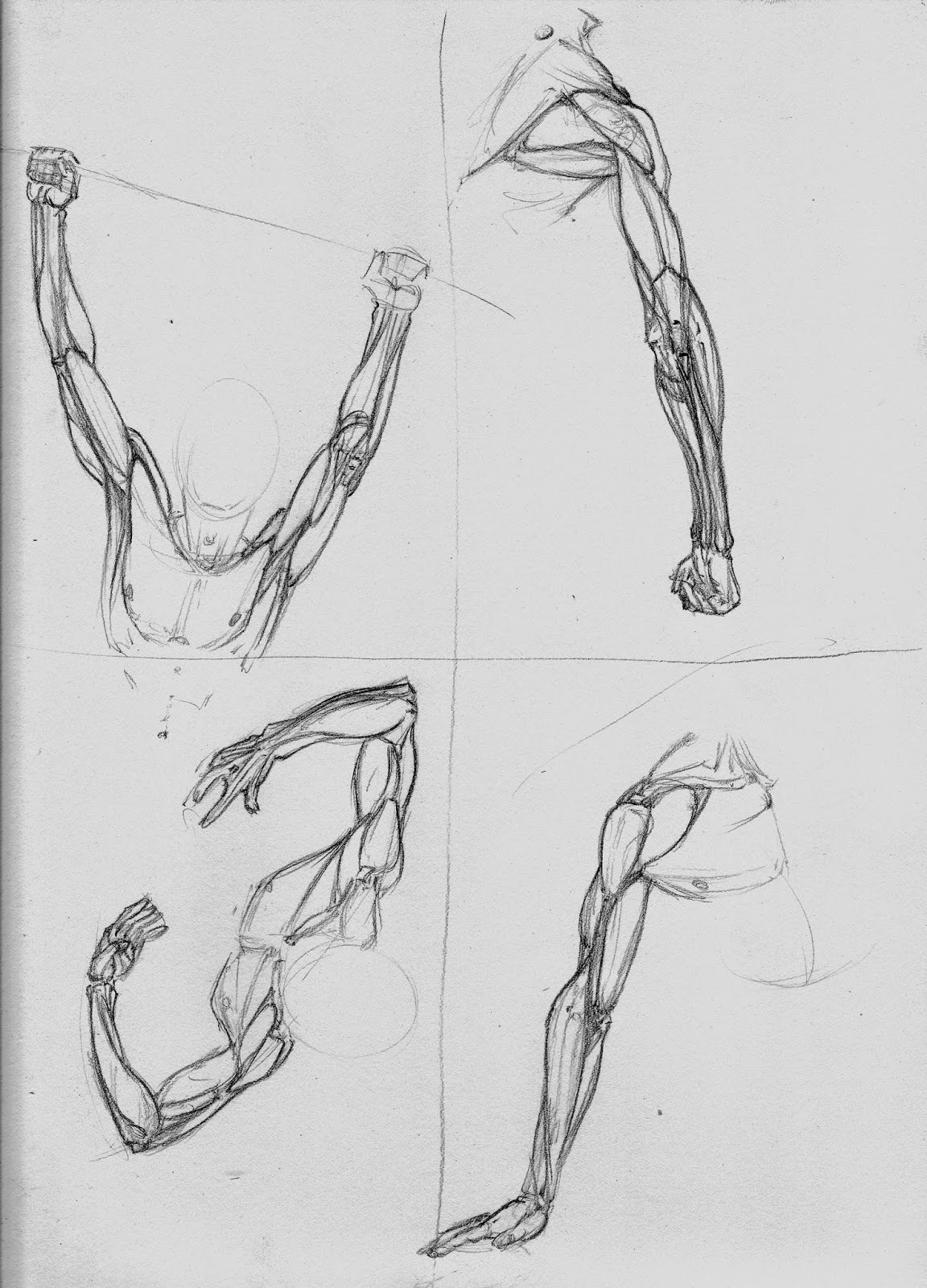

would make learning the rest of this stuff (anatomy, planes, and shading) more

difficult. So, I’ve decided to put it off until I’m comfortable with the more

encyclopedic details. I’ll reach a point (and I’m almost there) where I’ll look

at my figures and think, ‘The

construction is accurate, but the texture makes this a sloppy representation.’

That’s when I’ll be done learning construction and be able to focus fully on

technique.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)